Why Black Friday is a Prisoner’s Dilemma

Why companies keep falling for it and how to escape the trap

Black Friday is one of the biggest contradictions in business.

Companies know it destroys margin. They complain about it. They hate the planning. Yet they do it every single year.

It makes no economic sense.

But it makes perfect sense through the lens of Game Theory.

This is where the original Prisoner’s Dilemma explains everything about this modern sales event.

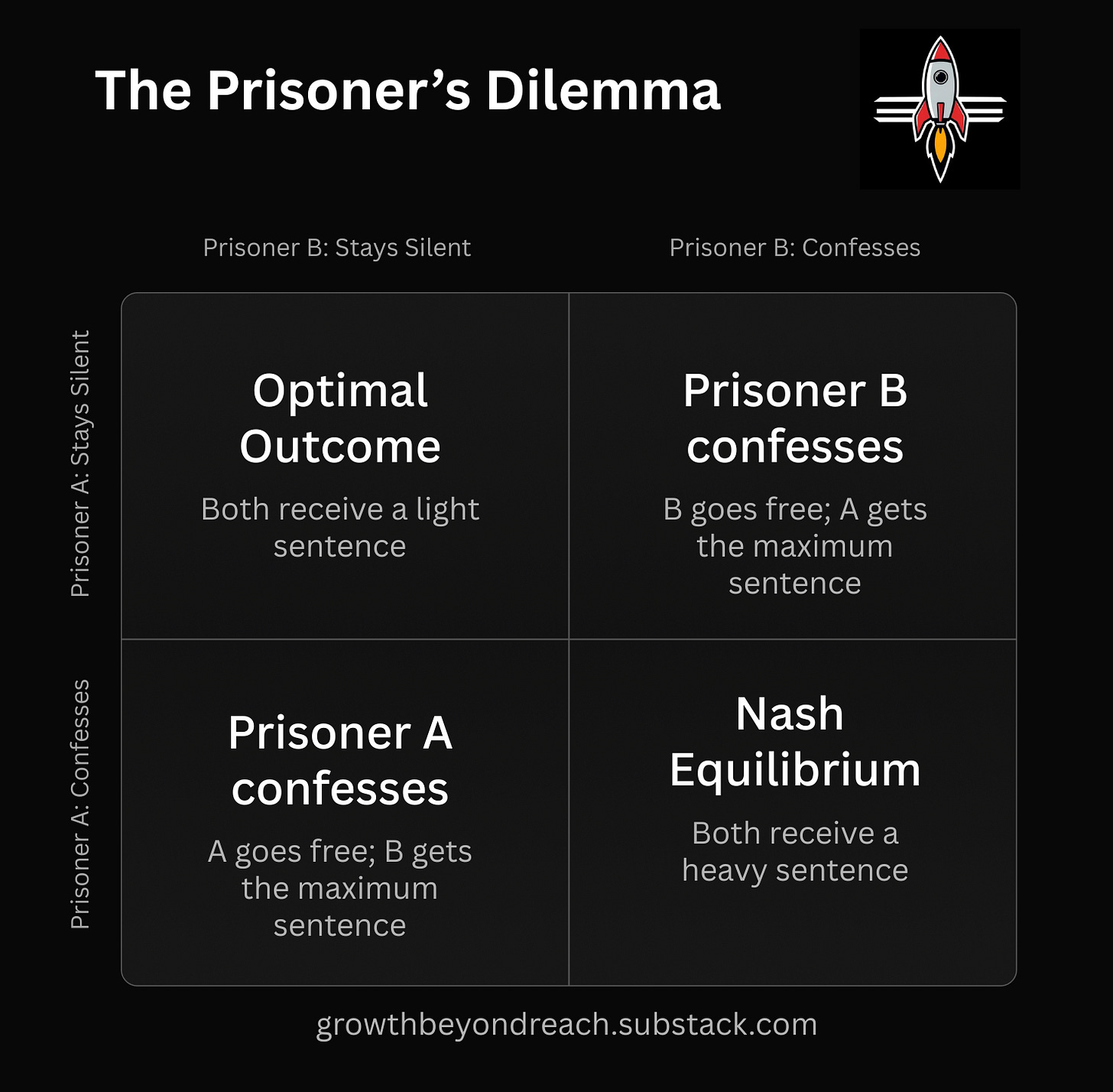

What the Prisoner’s Dilemma actually means

Two criminals are arrested. The police separate them. Each one is offered the same deal:

• If both stay silent, they both receive light sentences

• If one confesses and the other stays silent, the confessor goes free and the silent one gets the maximum sentence

• If both confess, they both receive heavy sentences

The rational move for each prisoner is to confess.

They protect themselves.

But when both follow their rational strategy, they end up with a worse outcome.

Individual rationality creates collective irrationality.

That is the core idea.

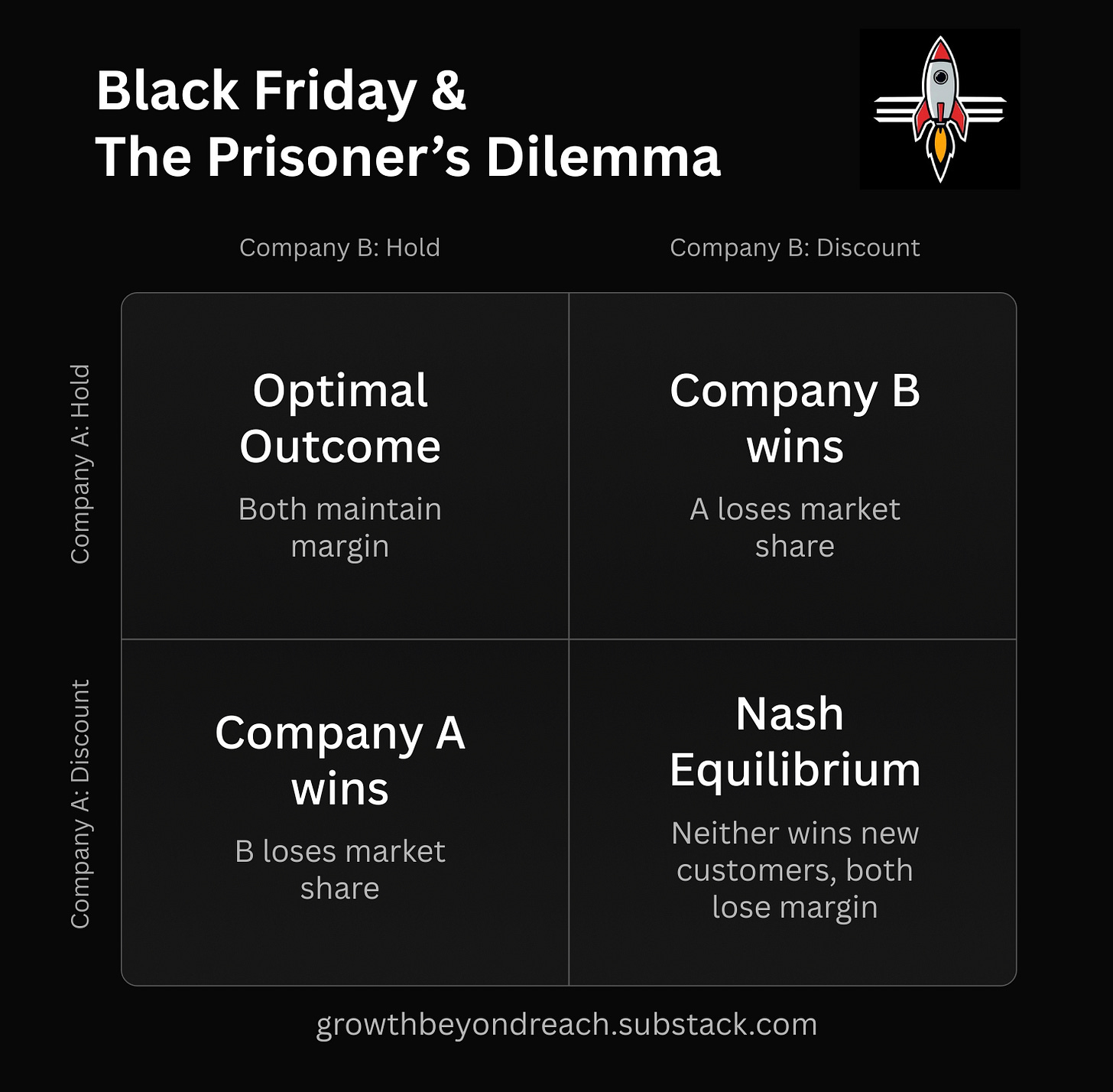

Why Black Friday works exactly the same

Imagine two competing brands, A and B.

They each have two options: 1. Hold prices, 2. Discount aggressively.

Three scenarios:

If both hold, they both maintain margin.

If one discounts and the other holds, the discounter steals customers and market share.

If both discount, they protect share but destroy margin.

Each company wants to avoid the worst outcome:

being the only one that doesn’t discount.

So the dominant strategy becomes discounting, even though it hurts everyone.

This outcome is called the Nash equilibrium.

It is the point where neither player can unilaterally change strategy without making themselves worse off.

Both discount. Both hate the result. And… both repeat it anyway.

Why Black Friday no longer works economically

Black Friday once made sense because only a few brands participated.

There was differentiation. The economics worked.

Now everyone does it.

It has become a zero sum game with lower margins and no real advantage.

Most Black Friday revenue is not incremental.

It is pulled forward from December or January, often at lower margin.

Don’t be fooled by the increase in topline. It’s the contribution margin that matters.

How brands can escape the trap

The Prisoner’s Dilemma is powerful, but it’s possible to escape.

Below are the three ways companies break free from the discounting equilibrium.

1. Differentiate your payoff function

If your brand value and customer relationship don’t rely on price, you’re not playing the same game anymore. You’ve changed the incentives.

Examples:

Apple rarely discounts its core products. Their “Black Friday” offers are gift cards, never real price cuts.

Patagonia avoids heavy discounting entirely and focuses on mission, durability, and repair.

Arc’teryx maintains premium positioning by keeping discounts minimal and tightly controlled.

When price is no longer the main lever, competitors can discount all they want.

You’re not in that game.

2. Change the rules of the game

If you can’t win the existing game, create a new one.

Examples:

Alibaba created Singles’ Day, a shopping event bigger than Black Friday, shifting attention to a date they control.

Amazon built Prime Day, turning discounting into a loyalty event only for members.

Sephora uses private member sales, where heavy discounts are offered only to Beauty Insider tiers, not the broad market.

Creating your own event resets expectations and moves competition onto your terms.

3. Reduce discounting frequency overall

Black Friday happens once a year, but many brands discount constantly. This is what traps them in a repeated prisoner’s dilemma.

The escape is to stop training customers to wait for sales.

Examples:

Lululemon discounts very selectively and uses “We Made Too Much” only for slow movers, not core products.

Nike increasingly reserves discounts for its own DTC channels, building loyalty while reducing broad-market promo dependency.

Rolex, Chanel, and most luxury houses maintain pricing power because they barely discount, ever. Black Friday or otherwise.

When discounting becomes rare and intentional, Black Friday becomes a controlled operational lever instead of a dependency.

The bottom line

Black Friday is a perfectly rational decision that creates an irrational collective outcome.

The brands that win long term do not play the game by default.

They change the incentives.

They change the rules.

They change the frequency.

And they protect their margins while everyone else races to the bottom.

If you found this useful, feel free to share it with someone planning their Q4 promo calendar. It might save them a lot of margin.

And please do let me know you enjoyed this post by liking, commenting or responding.

It’s a small gesture, but it keeps me motivated to write.